Unlock the Hidden Power of Sensory-Specific Satiety to Outsmart Your Cravings and Supercharge Your Wellness Journey

Ever found yourself wondering why the tenth bite of chocolate doesn’t quite thrill you the way the first did? It’s not just your sweet tooth playing tricks – it’s a fascinating biological phenomenon called sensory-specific satiety, where our brains get a bit tired of the same flavor after a while. This quirky mechanism nudges us to switch up our plates, helping our bodies cover their nutritional bases. But here’s the kicker: what if we could turn this natural tendency to our advantage? Imagine using the very thing that dulls our enthusiasm for repeated tastes to actually help manage hunger and even weight. Sounds almost too good to be true, right? Well, from the surprising satiety power of humble boiled potatoes to the counterintuitive success of ‘mono diets,’ there’s a lot more to this than meets the eye — and plenty to chew on when it comes to making smarter food choices that satisfy both body and mind. LEARN MORE

How can we use sensory-specific satiety to our advantage?

When we eat the same foods over and over, we become habituated to them and end up liking them less. That’s why the “10th bite of chocolate, for example, is desired less than the first bite.” We have a built-in biological drive to keep changing up our foods so we’ll be more likely to hit all our nutritional requirements. The drive is so powerful that even “imagined consumption reduces actual consumption.” When study participants imagined again and again that they were eating cheese and were then given actual cheese, they ate less of it than those who repeatedly imagined eating that food fewer times, imagined eating a different food (such as candy), or did not imagine eating the food at all.

Ironically, habituation may be one of the reasons fad “mono diets,” like the cabbage soup diet, the oatmeal diet, or meal replacement shakes, can actually result in better adherence and lower hunger ratings compared to less restrictive diets.

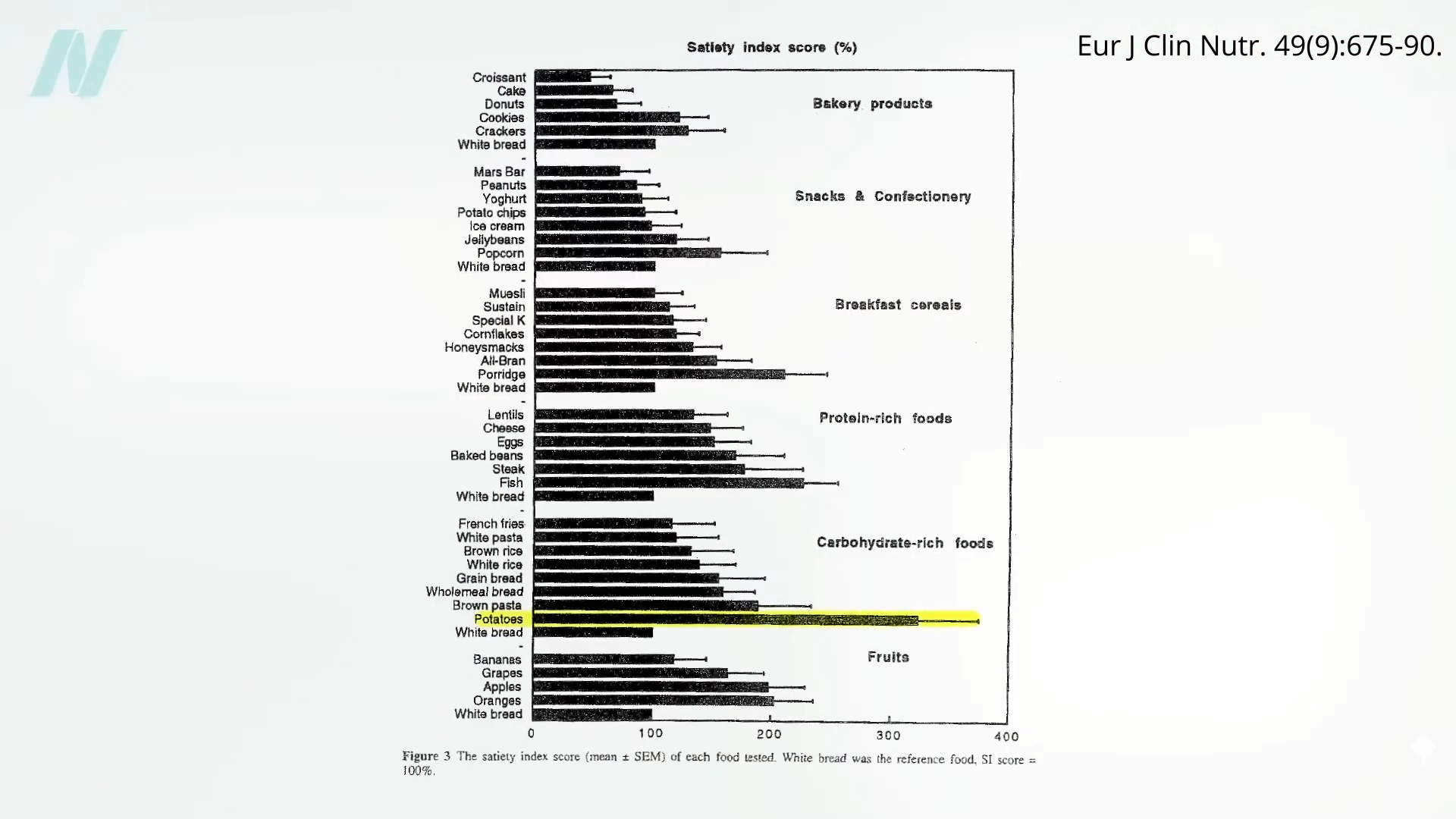

In the landmark study “A Satiety Index of Common Foods,” in which dozens of foods were put to the test, boiled potatoes were found to be the most satiating food. Two hundred and forty calories of boiled potatoes were found to be more satisfying in terms of quelling hunger than the same number of calories of any other food tested. In fact, no other food even came close, as you can see below and at 1:14 in my video Exploiting Sensory-Specific Satiety for Weight Loss.

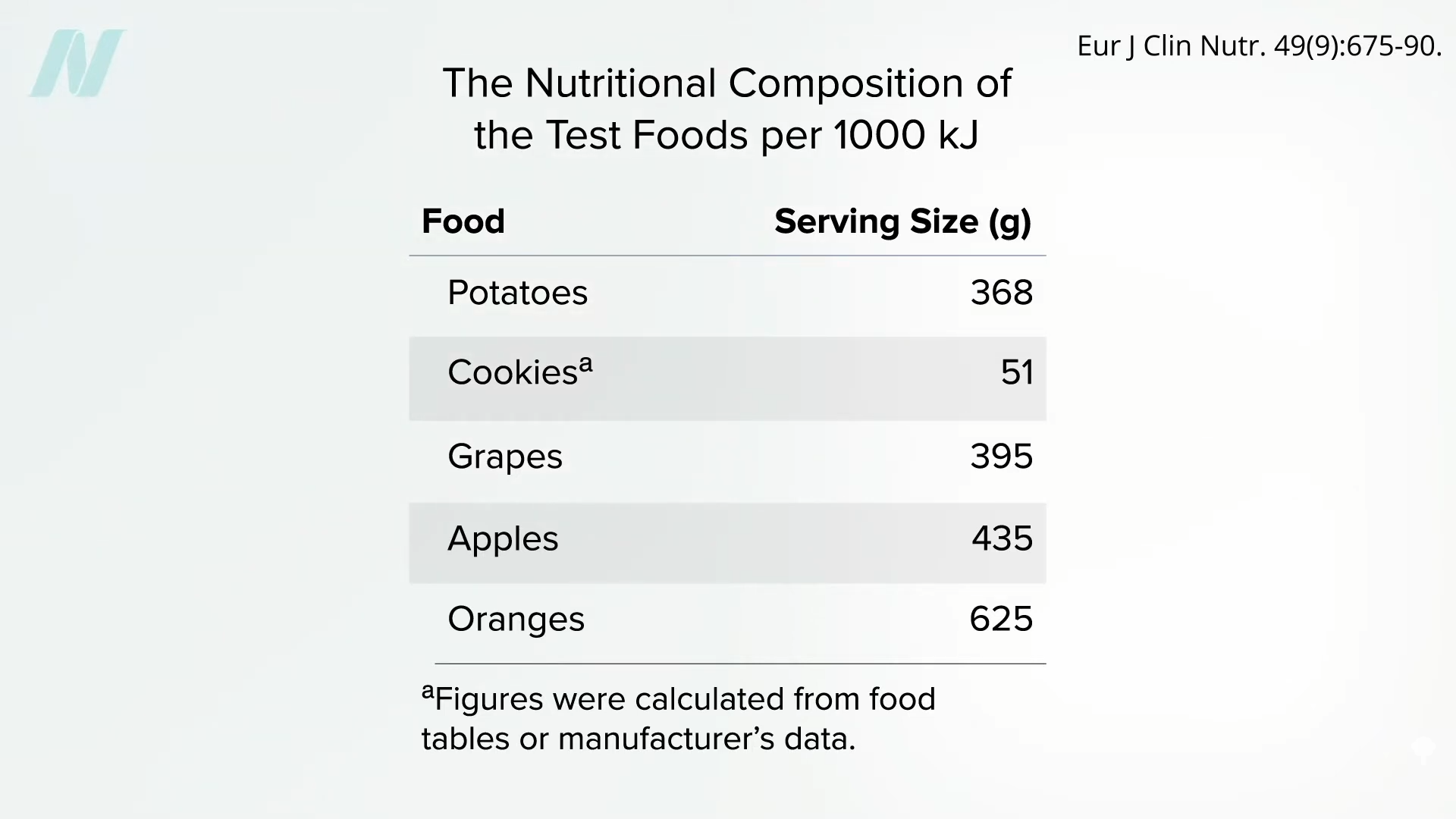

No doubt the low calorie density of potatoes plays a role. In order to consume 240 calories, nearly one pound of potatoes must be eaten, compared to just a few cookies, and even more apples, grapes, and oranges must be consumed. Each fruit was about 40 percent less satiating than potatoes, though, as shown here and at 1:45 in my video. So, an all-potato diet would probably take the gold—the Yukon gold—for the most bland, monotonous, and satiating diet.

A mono diet, where only one food is eaten, is the poster child for unsustainability—and thank goodness for that. Over time, they can lead to serious nutrient deficiencies, such as blindness from vitamin A deficiency in the case of white potatoes.

The satiating power of potatoes can still be brought to bear, though. Boiled potatoes beat out rice and pasta in terms of a satiating side dish, cutting as many as about 200 calories of intake off a meal. Compared to boiled and mashed potatoes, fried french fries or even baked fries do not appear to have the same satiating impact.

To exploit habituation for weight loss while maintaining nutrient abundance, we could limit the variety of unhealthy foods we eat while expanding the variety of healthy foods. In that way, we can simultaneously take advantage of the appetite-suppressing effects of monotony while diversifying our fruit and vegetable portfolio. Studies have shown that a greater variety of calorie-dense foods, like sweets and snacks, is associated with excess body fat, but a greater variety of vegetables appears protective. When presented with a greater variety of fruit, offered a greater variety of vegetables, or given a greater variety of vegetable seasonings, people may consume a greater quantity, crowding out less healthy options.

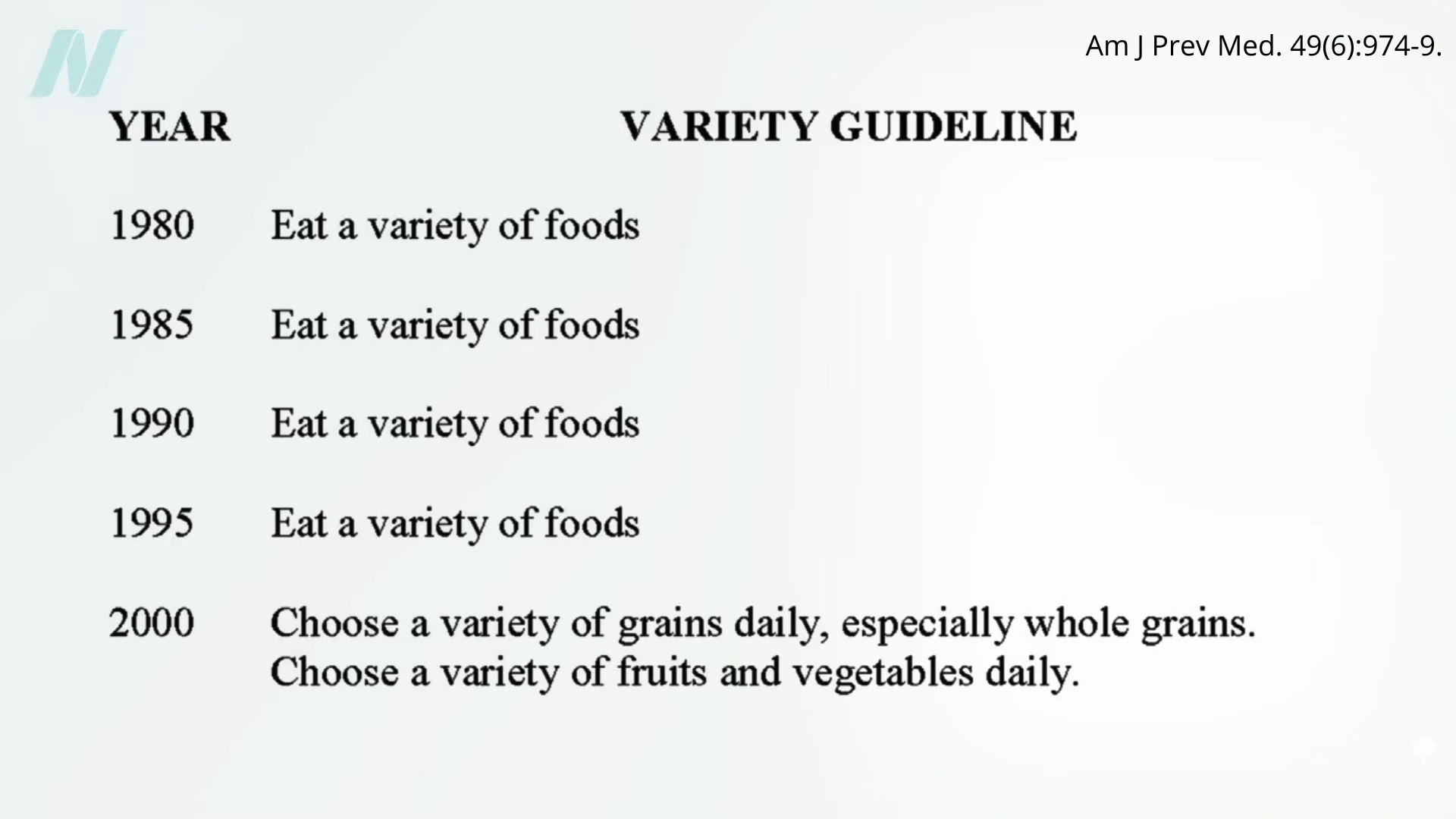

The first 20 years of the official Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommended generally eating “a variety of foods.” In the new millennium, they started getting more precise, specifying a diversity of healthier foods, as seen below and at 3:30 in my video.

A pair of Harvard and New York University dietitians concluded in their paper “Dietary Variety: An Overlooked Strategy for Obesity and Chronic Disease Control”: “Choose and prepare a greater variety of plant-based foods,” recognizing that a greater variety of less healthy options could be counterproductive.

So, how can we respond to industry attempts to lure us into temptation by turning our natural biological drives against us? Should we never eat really delicious food? No, but it may help to recognize the effects hyperpalatable foods can have on hijacking our appetites and undermining our body’s better judgment. We can also use some of those same primitive impulses to our advantage by minimizing our choices of the bad and diversifying our choices of the good. In How Not to Diet, I call this “Meatball Monotony and Veggie Variety.” Try picking out a new fruit or vegetable every time you shop.

In my own family’s home, we always have a wide array of healthy snacks on hand to entice the finickiest of tastes. The contrasting collage of colors and shapes in fruit baskets and vegetable platters beat out boring bowls of a single fruit because they make you want to mix it up and try a little of each. And with different healthy dipping sauces, the possibilities are endless.

Post Comment