Unlocking ‘Star Trek Phase II’: The Untold Story of the Lost Series That Revolutionized a Galactic Empire!

Have you ever wondered why a cultural phenomenon like Star Trek, which skyrocketed in popularity after its 1969 cancellation, took nearly two decades to fully blast back onto our screens? It’s kind of a head-scratcher, right? I mean, with the overwhelming fan devotion and the buzz that never quite died down, you’d think the original Enterprise crew would’ve beamed back into our living rooms way sooner. Instead, it took a whole eight years after the 1979 film before Star Trek: The Next Generation boldly went where no one had gone in a while—back on TV. But here’s a kicker—a nearly forgotten chapter in the Star Trek saga: Star Trek II, aka Phase II, was ready to launch in the late ’70s with the original cast poised for a reunion—well, almost everyone, except for the iconic Leonard Nimoy as Spock. This tantalizing “what if” could have reshaped the franchise’s trajectory far earlier than we realize. So, what happened to this ambitious revival? Let’s dive into the twists, turns, and near-misses that almost brought the Enterprise back to the small screen before it took off for the big one. LEARN MORE.

Given the phenomenal success Star Trek enjoyed in the years between its cancellation in 1969 and the release of Star Trek: The Motion Picture a decade later, you’d think it would have been a no-brainer to bring the franchise back to television sooner. Instead, it took eight long years from the film before fans finally got Star Trek: The Next Generation in 1987. What many forget—or never knew—is that the Enterprise crew almost returned much earlier, in the form of a weekly show called Star Trek II. These days it’s more commonly referred to as Star Trek: Phase II, but in 1977 it was very real and very much in motion, with the original cast set to reunite—everyone, that is, except Leonard Nimoy as Spock.

Throughout the 1970s, Paramount flirted with different ways to revive the franchise, but Star Trek II came the closest to becoming a reality. Announced just a month after the release of Star Wars, the project actually went into pre-production. Sets were being built, scripts commissioned and even new characters cast. For the first time since the original series went off the air, the Enterprise was on the verge of making its way back into living rooms.

A big part of the push came from Barry Diller, then head of Paramount Pictures. Diller was chasing a dream he’d had for years: launching a fourth television network to compete with ABC, CBS, and NBC. (It was a dream he would eventually fulfill a decade later with Fox Broadcasting.) As part of his strategy, Paramount began courting independent stations around the country, offering them a Saturday-night programming package anchored by Star Trek II.

Robert Goodwin, who had been assistant to Paramount executive Arthur Fellows, was brought in as Director of Development for one of Paramount’s newest acquisitions, Playboy Enterprises. He recalled how things were supposed to work:

“The plan was that every Saturday night, they were going to do one hour of Star Trek and a two-hour movie,” Goodwin explained. “My interest had always been more in the long form rather than the series side of television. Nardino decided that he was going to put me in charge of all these two-hour movies, which was great for me.”

At that point, studio forces pulled Robert Goodwin—who years later would become a producer on The X-Files—away from his development assignment and transferred him directly into the Star Trek offices. Meanwhile, creator Gene Roddenberry was growing increasingly energized. After years of pushing against the tide, his seemingly endless battle to bring Star Trek back had finally paid off. Now he had the chance not just to revive his creation, but to see if lightning could strike twice—though in his view, it was never about competing with himself.

“Those [original] episodes will always be there for what people want to make out of them,” he said at the time. “We’re making a new set of them 10 years later under very different circumstances. Neither takes away from the other. The worst that can happen is someone would say that Roddenberry couldn’t do it a second time. That doesn’t bother me, as long as I did my damnedest to do it a second time.”

Things move forward

Star Trek II was quickly becoming a very real project for everyone involved. But assembling the right creative team was critical.

“They were looking for someone to come on as producer,” Goodwin recalled. “And Gene Roddenberry had heard about me. To be perfectly honest, I wasn’t anxious to do it and was pretty much strong-armed to do the show and not given too much of a choice. Paramount said, ‘Forget the movies, you’re doing Star Trek.’ To make a long story short, [Roddenberry] wanted me to go in as one of two producers. They were going to hire a writing producer and a production producer. It was a strange situation.”

Roddenberry eventually found his “writing producer” in Harold Livingston, a novelist and TV writer who would later pen the screenplay for Star Trek: The Motion Picture.

“I had never paid much attention to Star Trek,” Livingston admitted with a sheepish smile. “I had always considered it something of a media event. I was totally unwashed. But I wanted to make it more universal. I felt that Star Trek, its success notwithstanding, had a restrictive audience. There was a greater audience for it and my broad intention was to create a series that would attract a larger audience by offering more. We would still offer the same elements as the original Star Trek, i.e. science fiction and hope for the future, and then do realistic stories.”

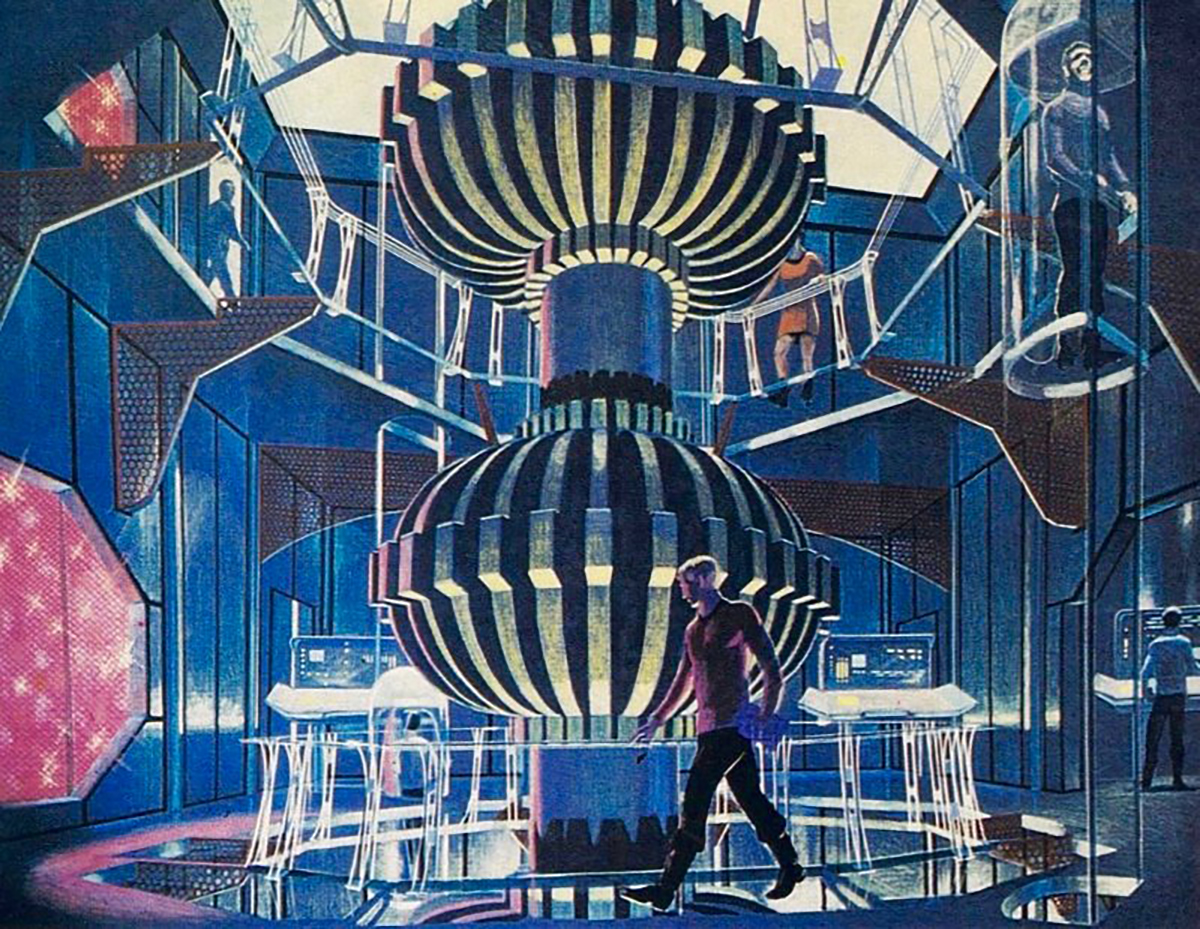

Concept designer Mike Minor’s initial take on the new Enterprise

“I just thought they had reached a certain barrier with it. How much could you do before it becomes totally redundant? They had so many stories which, to manipulate or move the plot, this goofy thing appeared out of nowhere. I’m thinking specifically of some Greek with an echoing voice that came on at the end and saved them. That was done too often. I wanted scripts that were interesting, made sense and moved from a literary standpoint. Anyway, 13 episodes plus a pilot were ordered and it was then my job to develop these stories, which I set upon doing.”

With that mandate, Harold Livingston rolled up his sleeves. But he also knew he needed someone who understood Star Trek inside and out. To help ground his efforts, he turned to Jon Povill, Gene Roddenberry’s assistant. Povill would not only serve as story editor for the proposed series, but eventually step up as associate producer on Star Trek: The Motion Picture.

“Harold wasn’t very familiar with the old series at all,” Povill recalled, “and relied on me to be the monitor of whether something fit with Star Trek or not. Once everything got rolling, and we were in many writers’ meetings, I took over as the person who pointed out where there were holes in the stories and where they didn’t conform to what Star Trek was supposed to be.”

In with the new…

While behind-the-scenes production continued to take shape, scripts were also being developed to reflect a major absence: Mr. Spock. Leonard Nimoy was in dispute with the studio over issues such as merchandise royalties and made it clear he would not be returning. To fill that void, three new characters were created: Lt. Xon, a young full-blooded Vulcan stepping into the role of Enterprise Science Officer, who found himself living under the shadow of a “legend;” Commander Will Decker, son of Commodore Matt Decker (William Windom) from the original series episode “The Doomsday Machine,” as First Officer; and Lt. Ilia, a bald, empathic Deltan navigator with ESP abilities.

Of the trio, Decker and Ilia ultimately survived the transition from television to film, appearing in Star Trek: The Motion Picture—though not quite as originally envisioned. The movie quickly establishes that the two had a past romantic relationship, which had not been part of the plan for the series. Ilia remained largely intact as conceived, but Decker’s personality and role were significantly altered.

On television, viewers would have seen a gradual father-son dynamic develop between Decker and William Shatner‘s Kirk, as the younger officer was slowly groomed for command. Decker was also expected to lead many of the landing parties, leaving Kirk to remain aboard the Enterprise and carry the dramatic weight from that perspective. It was a structural choice not unlike the dynamic that would eventually define The Next Generation between Captain Picard and First Officer Riker.

“The original series had 79 episodes,” Jon Povill noted, “and therefore many things had already been done. The challenge was coming up with things that weren’t repeats of ideas already explored. What we were definitely striving for on the show was doing things that were different, and I think by and large, we were successful. That was the biggest challenge: coming up with things that were fresh and were also Star Trek. The characters of Xon, Decker and Ilia would have helped in this area. We wanted characters who could go in new directions, as well as the old crew.”

“I particularly liked Xon,” he added. “I thought there was something very fresh in having a nice young Vulcan to deal with; somebody who was trying to live up to a previous image. That, to me, was a very nice gimmick for a TV show that was missing Spock. But we never wanted Xon to be a Spock retread. We wanted him to be somebody who definitely had his own direction to go in and he had different failings than Spock. Also, he didn’t have Spock’s neurosis regarding his human half. As far as Xon was concerned, Spock had a distinct advantage in being half-Vulcan and half-human in the context of where he was, what he was doing and where he was working. If he was on Vulcan, it wouldn’t have been an advantage, but to be living with humans, it really helped. Xon’s youth was also very important and he would have brought a freshness that people would have appreciated.”

“Ilia was sort of an embodiment of warmth, sensuality, sensitivity and a nice Yin to Xon’s Yang. Decker, of course, was a young Kirk. I think he would have been the least distinct. He would have had to grow, and the performance probably would have done that, bringing something to Decker that the writers would have ultimately latched on to for material. He’s the one who would have had to develop more through the acting and performance than the other two. Xon and Ilia were concept characters. They would have developed, too, I’m sure, because characters grow when they’re performed much more than they do from just the writing. In the early writing, you don’t realize the full potential. You don’t know who’s going to play the character, how they’re going to play it and what the characteristics of their performance are going to be. If you look at ‘The Menagerie’ from the original series, for example, Spock actually laughs.”

The man who would be Xon

During pre-production, casting began to take shape. Indian actress Persis Khambatta was chosen to play Ilia—a role she would eventually bring to life in the first feature film—while New York stage actor David Gautreaux was cast as Xon.

“When I got the role,” Gautreaux reflected, “I actually went off on a meditative trek and fasted for 10 days. I allowed my hair to grow long. I started researching to be a Vulcan with no emotion. For an actor, that’s death. How do you appear as having no emotions without looking like a piece of wood? That was my acting objective.”

“In all honesty, I was looking forward to playing Xon. His actions were tremendous as well as his strength without size and the aspect of playing a full Vulcan. When I say that, I mean a more involved presence on the show and the running of the ship. It was a very exciting premise to be playing. To me, it was a potentially good gig that didn’t work out.”

While Gautreaux was preparing for the role, scripts were coming in and director Bob Collins had been signed to helm the two-hour premiere episode. That story, based on Alan Dean Foster’s treatment “In Thy Image,” centered on a NASA space probe that returns to Earth centuries later, having gained sentience and searching for its creator. Fans would later recognize this as the foundation for Star Trek: The Motion Picture.

“At that point,” recalled Robert Goodwin, “they had spent about four years trying to get a script for a feature, but they couldn’t come up with anything that [executive] Michael Eisner liked. We had various options on the two-hour thing and I suggested to Gene that since it had never been done in the series before, we should come up with a story in which Earth was threatened. In all the previous Star Trek episodes, they never came close to Earth.”

In Thy Image looked like the perfect solution.

“I remember,” Goodwin added, “that one day we went into the administration building. At this big meeting, there was (then-Paramount, now-Disney execs) Michael Eisner and Jeff Katzenberg, Gary Nardino, Gene, me and a bunch of other people. In that meeting, I got up and pitched this two-hour story. Eisner slammed his hands on the table and said, ‘We’ve spent four years looking for a feature script. This is it! Now, let’s make the movie.’”

‘Star Trek: The Motion Picture’

The transformation of Star Trek II from a television series into a feature film came down to a convergence of factors. Paramount’s ambitious plan to launch its own network fell apart when the studio couldn’t sell enough advertising to compete with the established “Big Three” broadcasters. At the same time, the landscape of science fiction had changed almost overnight. Star Wars had exploded into a cultural juggernaut in 1977, and Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind quickly followed with its own box office triumph. Suddenly, science fiction wasn’t just viable on the big screen—it was hot.

“When ‘In Thy Image’ became a feature,” explained director Bob Collins, “we were given a budget of about $8 million. Somewhere around that time, we were talking about special effects. Close Encounters was about to open, and the word around town was that it was spectacular. So, Roddenberry and I went down to the Pacific Theater and sat down for what I think was a noon performance. We came out, both pretty blown away by Close Encounters. I turned to him and said, ‘Well, there goes our low budget special effects.’ After Star Wars and Close Encounters, you couldn’t do low budget special effects anymore. That meant a whole new way of thinking and a whole reorganization of the production and concepts. They needed a great deal more money and time and there were only a few people who could do it.”

Collins’ words would prove prophetic. The budget ballooned from $8 million to $20 million (and would ultimately reach $44 million), and with it came a creeping realization that his role might not last.

“We were preparing to make this picture,” he admitted, “but the writing was on the wall. I was a television director who hadn’t done a feature film at that time. It was evident that they were going to hire somebody who had done a feature and was used to working with big budget special effects. Paramount wasn’t brave about such things, so I called up Jeff Katzenberg and said, ‘You’re going to replace me, right?’ He said, ‘No, Bob, never. Take my word for it, Bob. Trust me.’”

This was the moment the project truly pivoted. Star Trek II had started as the cornerstone of a fledgling television network, but in the shadow of Star Wars and Close Encounters, it was being reshaped into a big-screen epic—and the people guiding it would soon change along with it.

“Then my agent,” Collins recalled, “who at that time handled Robert Wise, called up and said, ‘Look, we’ve got an offer for Robert Wise to replace you on the picture.’ Apparently Paramount couldn’t remember that we both had the same agent, so I called up Jeff again and said, ‘Look, are you going to replace me?’ He said, ‘Absolutely not! Never! You’re absolutely staying with the project.’ I pointed out that Robert Wise and I had the same agent, so he said, ‘If Robert Wise doesn’t do it, then you are absolutely going to do it.’ I laughed about that for a while. I knew it would happen sooner or later, but I was more angry about the way it happened.”

Collins was quick to stress that his frustration wasn’t aimed at Gene Roddenberry.

“Gene would often say about the script, ‘This isn’t Star Trek.’ One could argue that it may not be Star Trek, but it’s good and at the same time you had to realize that on a personal level, he was wrapped up in it. His whole way of defining himself was involved with the series and with this project. I don’t think any of us ever felt very angry at him. We wanted to help him realize his ambition and we wanted to make a good picture, too. Paramount was holding a gun to his head, saying that they were going to do it, and then they weren’t going to do it. That tension, I think, flowed through all of us. But I liked Roddenberry and I always felt sympathetic towards him and the project.”

Saying goodbye

Robert Goodwin didn’t fare much better once Robert Wise was brought aboard.

“When they went with Robert Wise as director,” Goodwin recalled, “Gene and I were never really informed of what the steps of the deal were. It turns out that Robert Wise is used to producing and directing, so I was asked by Gene and the studio if I would stay on as associate producer. I didn’t want to spend a minute of my life doing that. I was an associate producer 10 years earlier and it was like taking a step backwards, especially facing two years of production. So I left.”

David Gautreaux soon followed him out the door. Wise—whose credits ranged from The Day the Earth Stood Still to The Sound of Music—had identified what he felt was missing from the project. He reportedly asked what key ingredient hadn’t been secured, and when he was told, he insisted the issue be resolved. The missing piece, of course, was Leonard Nimoy as Mr. Spock. At Wise’s urging, Paramount mended fences and got Nimoy back on board.

When Leonard Nimoy officially signed on to the project, David Gautreaux realized that his time as Xon was over.

“I was doing a play at the time,” Gautreaux recalled, “trying not to think that I was going to be playing an alien for the rest of my life. Then, I spoke to Gene Roddenberry and said, ‘What’s the story? Did you see that Leonard Nimoy is coming back to play his character? What’s going to happen to Xon?’ He said, ‘Oh, Xon is very much a part of the family and you’re very much a part of our family.’ I responded, ‘Gene, don’t allow a character of this magnitude to simply carry Spock’s suitcases on board the ship and then say, ‘I’ll be in my quarters if anybody needs me.’ Give him what I’ve put into him and what you’ve put into him. If he’s not going to be more a part of it and more noble than that, let’s eliminate him.’ And that’s what we did.”

With that, the voyages of Star Trek II ended before they ever truly began. In March 1978, Paramount held one of the largest press conferences in Hollywood history to announce that production was officially underway on Star Trek: The Motion Picture. After years of false starts, scrapped pilots and abandoned revivals, the long and winding road to bring Star Trek back had finally reached its destination. On December 7, 1979, fans would witness the rebirth of the franchise when the Enterprise returned—this time, on the big screen.

Looking back, it’s striking how much of Star Trek II—or Phase II, as fans now know it—never really disappeared. Decker and Ilia made their way into The Motion Picture, while storylines and character dynamics first imagined for the aborted series would later resurface in The Next Generation. Even Xon, though erased from canon, left a conceptual fingerprint that can be felt in the cool logic of characters like Data. In many ways, Phase II became a ghost series, living on not in syndication or box sets, but in the DNA of what followed.

So while the television series itself never materialized, its spirit shaped the path forward. The Motion Picture launched the franchise onto the big screen, The Next Generation reignited it on television, and the influence of the unmade Phase II quietly bridged the gap between them. It remains one of those tantalizing “what ifs” in television history—but one whose presence is still felt every time the Enterprise sets out on another voyage.

Post Comment