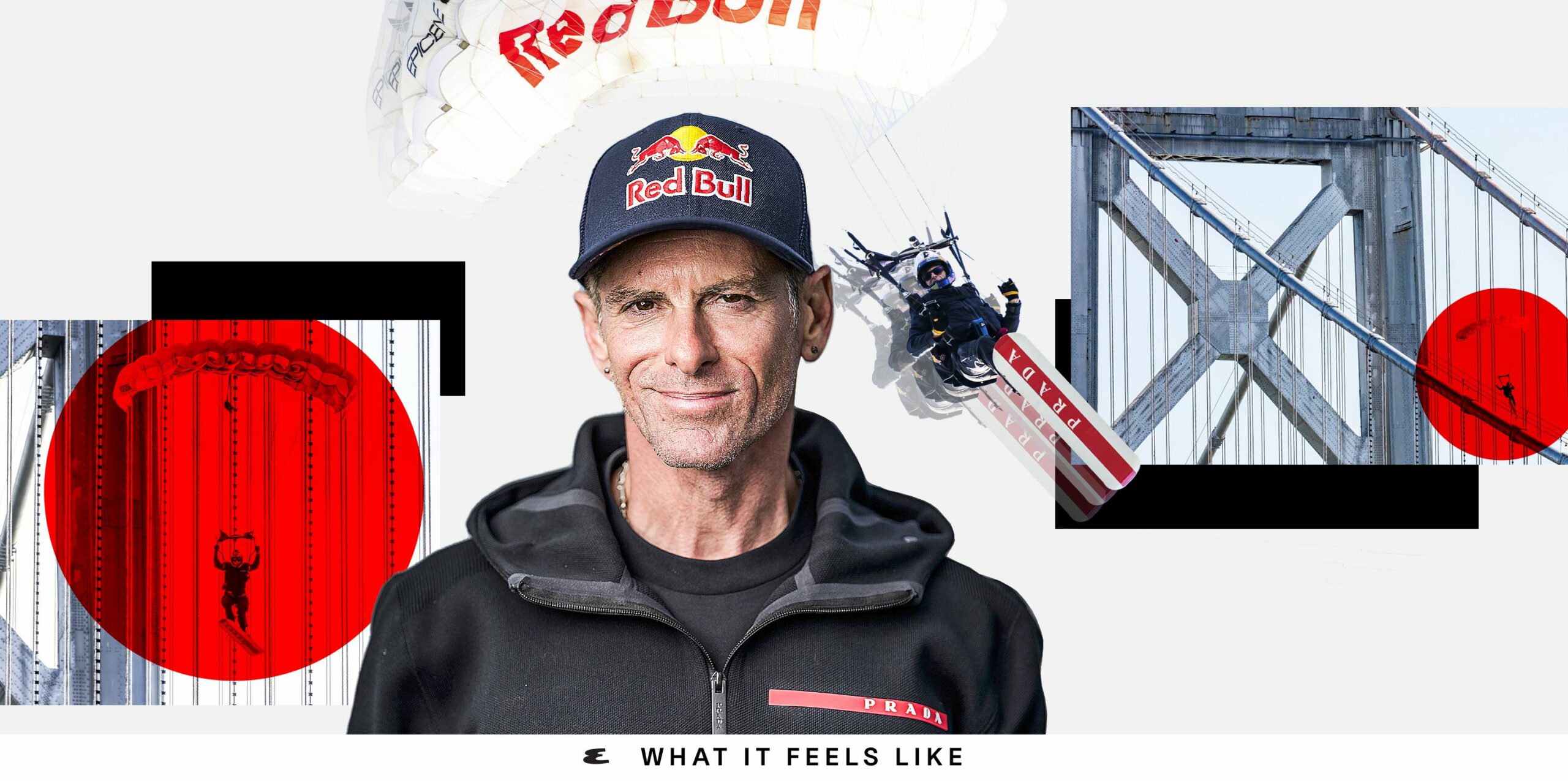

At 50, This Skysurfer Defied Gravity and Age—The Stunt That Could Change Everything You Thought About Limits

Ever caught yourself wondering what it’d feel like to strap a board to your feet and soar through the sky like some superhero? Well, that’s exactly what Sean MacCormac lives every single day — except he didn’t just wake up owning the skies. Nope, Sean had to fib a bit (okay, a lot) about his experience just to even get a shot at training with the legendary Jerry Loftis, America’s sole skysurfing guru. Imagine bluffing your way through a sport that demands insane skill and guts, only to find out you’ve got a natural knack that blows everyone’s expectations right out of the atmosphere. From mastering tricks that should’ve taken months in mere hours, to spinning like a human tornado at twelve revolutions per second, this guy’s tale is a wild ride of audacity, passion, and a board so finely tuned it’s practically part of his soul. And if grinding 60 feet of the San Francisco Bay Bridge’s cable from a helicopter leap into the unknown doesn’t get your pulse racing, what will? This isn’t just about flying — it’s about becoming one with the sky, bending the rules, and redefining what’s possible. Ready to jump in? LEARN MORE

Sean MacCormac; 50; Skysurfer

When I called Jerry Loftis, the only guy in America teaching skysurfing, he said I needed 500 jumps to train with him. I had maybe eighty. “Of course,” I lied. “I’ve done that.” He said I needed to be an accomplished sit flyer. “Oh, I definitely can do that,” I lied again, then went to look up what sit flying was.

Skydiving isn’t exactly an area where you should pad your resume, but it turned out to be supernaturally intuitive for me. Within hours, I was doing tricks that should have taken months to master. Jerry later found out I lied, forgave me, and we became great friends. When he passed away years later, I used his workshop to build one final board, the same kevlar-wrapped board with a honeycomb core I’ve been flying for the past twenty years.

This was after seeing a photo of Patrick de Gayardon skysurfing at eighteen and knowing instantly it was what I was meant to do. Skysurfing is the art of strapping a modified snowboard to your feet and using it to fly around the sky. Unlike regular snowboards, these are extremely rigid and light, more like airplane wings. You can use the board as either a propeller or a wing, shooting across the sky at 200 mph or rocketing down at 250 mph.

That board carried me through my X Games career, into the Red Bull Air Force, and even helped enable my “Invisible Man” power move, spinning at twelve revolutions per second for ten seconds straight. For this move, I had to make a homemade G-suit because all the blood would rush to my arms, causing capillary damage.

But skysurfing has always felt incomplete to me. Everyone kicks their board off before landing, treating it like disposable gear. I spent over a decade honing “hook turn” swooping techniques, diving at 70-plus mph, then converting that energy into forward momentum to skim just above the ground, just like skateboarding. I wanted to bring that ethos to skysurfing.

The idea for grinding the San Francisco Bay Bridge came during a base jump commercial in Los Angeles. I was sitting on a ledge, imagining grinding these massive urban structures. The Bay Bridge, with its suspension cables stretched like rails across the sky, looked like the most natural skate structure imaginable.

Getting permission took eighteen months. I needed coordination between CalTrans, the Coast Guard, and half a dozen agencies. They gave us five minutes on a Saturday at 6 a.m.—minimal traffic, smallest chance of accidents. They’d stop traffic completely; They didn’t want drivers distracted by someone grinding a bridge cable twenty stories above them. Prada reimagined my board, bringing performance materials from their sailing partners and reinforcing it for the bridge.

The technical requirements were insane. Jump from a helicopter at 5,000 feet, open my chute with only 1,500 feet to set up my approach, about twenty-five seconds of decision-making time. Execute a hook turn that would double my speed into a dive at the bridge tower, then land on a three-quarter-inch steel safety cable. Grind the cable, dismount, and land on a floating barge. Miss by millimeters, and I’d slam into a steel rebar 200 feet above the road, 500 feet above water, with no time for a reserve chute.

The morning felt auspicious. The city looked incredible in early light, quiet except for our helicopter’s drumbeat. As we climbed, I could see the barge struggling against wind and tide, drifting from position. I’d have to adjust my approach on the fly.

When the helicopter door swung open, wind slapped me awake. Standing on my board on the skid, looking out over the Bay Bridge’s immensity, I felt electrified, seeing the whole sky, the ocean, this massive chunk of civilization calling to me. Twenty-two thousand previous jumps led to this moment. None of this was wasted on me.

Then I jumped.

When my chute opened, there were thirty seconds of pure peace, just me, my canopy, and the city spread below like a heavenly landscape. Then my helmet’s audible altimeter started beeping. Game time. My vision narrowed from wide appreciation to laser focus on one spot on that cable.

The approach from behind the tower meant I couldn’t see my target until the last second. When I finally made contact with that three-quarter-inch cable, the sound was otherworldly, like a pterodactyl screeching or like an interdimensional trumpet. You’re overwhelmed by crazy metallic grinding, but relieved because it’s working.

Out of the corner of my eye, I caught movement that snapped me out of my trance. The barge had shifted. I was about to miss my landing completely. I hammered a 180-degree turn off the rail, dove hard, and somehow managed an impromptu approach that let me power-slide into the barge’s center.

The grind lasted maybe four seconds, covering sixty feet of cable. By boarding standards, not record-breaking; I’d done longer in practice. But this wasn’t about distance. This was about taking something impossible and making it real.

People ask about the fear, the margins of error. There was performance anxiety, sure, with my family watching, Red Bull cameras everywhere. But the fear felt distant. Everything had synchronicity, like it was meant to happen. I’d been visualizing every detail for months through yoga and breath work, practicing on a crane at my home drop zone.

What it really feels like is harnessing something elemental. Ground-based board sports are about inertia—you jump and twist and throw your body around. Skysurfing is about understanding wind dynamics and harnessing that power. It’s not about conquering the sky; It’s about becoming part of it.

Post Comment