The Hidden Link Between Dietary Diversity and Overeating That Could Change How You Eat Forever

Ever wonder why your grocery cart mysteriously bulges with a dizzying variety of snacks, even when you thought you’d stick to your usual favorites? Well, there’s a sneaky reason behind that — and it’s not just your taste buds playing tricks on you. Our ancient brains evolved a clever survival hack: dietary diversity. It turns out, we humans are wired to crave a smorgasbord of flavors and textures to make sure we’re hitting all the nutritional bases. Sounds smart, right? But here’s the kicker — in today’s supermarket jungle, Big Food exploits this hard-wired desire for variety, turning it against us, making it way too easy to overeat. You see, variety doesn’t just keep meals interesting; it actually cranks up our calorie intake, sometimes by up to 60%! So, that tempting lineup of different chips, sodas, and desserts? It’s not just tempting — it’s designed to make us eat more. Intrigued? Let’s dig into how this biological quirk evolved to keep our ancestors alive but now risks packing on the pounds in an age of endless choices. LEARN MORE

Big Food uses our hard-wired drive for dietary diversity against us.

How did we evolve to solve the daunting task of selecting a diet that supplies all the essential nutrients? Dietary diversity. By eating a variety of foods, we increase our chances of hitting all the bases. If we only ate for pleasure, we might just stick with our favorite food to the exclusion of all others, but we have an innate tendency to switch things up.

Researchers found that study participants ended up eating more calories when provided with three different yogurt flavors than just one, even if that one is the chosen favorite. So, variation can trump sensation. They don’t call it the spice of life for nothing.

It appears to be something we’re born with. Studies on newly weaned infants dating back nearly a century show that babies naturally choose a variety of foods even over their preferred food. This tendency seems to be driven by a phenomenon known as sensory-specific satiety.

Researchers found that, “within 2 minutes after eating the test meal, the pleasantness of the taste, smell, texture, and appearance of the eaten food decreased significantly more than for the uneaten foods.” Think about how the first bite of chocolate tastes better than the last bite. Our body tires of the same sensations and seeks out novelty by rekindling our appetite every time we’re presented with new foods. This helps explain the “dessert effect,” where we can be stuffed to the gills but gain a second wind when dessert arrives. What was adaptive for our ancient ancestors to maintain nutritional adequacy may be maladaptive in the age of obesity.

When study participants ate a “varied four-course meal,” they consumed 60 percent more calories than those given the same food for each course. It’s not only that we get bored; our body has a different physiological reaction.

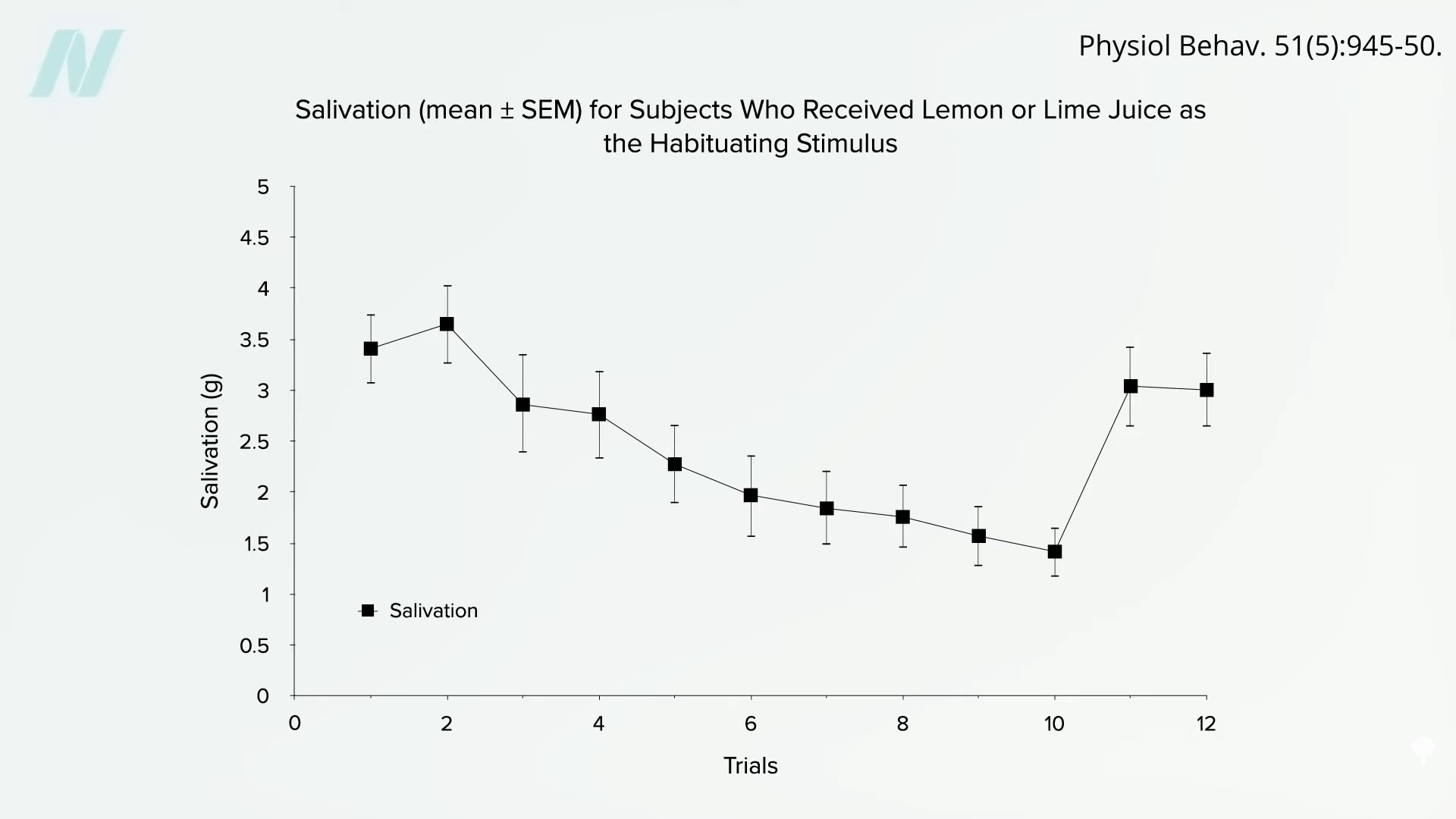

As you can see below and at 2:13 in my video How Variation Can Trump Sensation and Lead to Overeating, researchers gave people a squirt of lemon juice, and their salivary glands responded with a squirt of saliva. But when they were given lemon juice ten times in a row, they salivated less and less each time. When they got the same amount of lime juice, though, their salivation jumped right back up. We’re hard-wired to respond differently to new foods.  Whether foods are on the same plate, are at the same meal, or are even eaten on subsequent days, the greater the variety, the more we tend to eat. When kids had the same mac and cheese dinner five days in a row, they ended up eating hundreds fewer calories by the fifth day, compared to kids who got a variety of different meals, as you can see below and at 2:35 in my video.

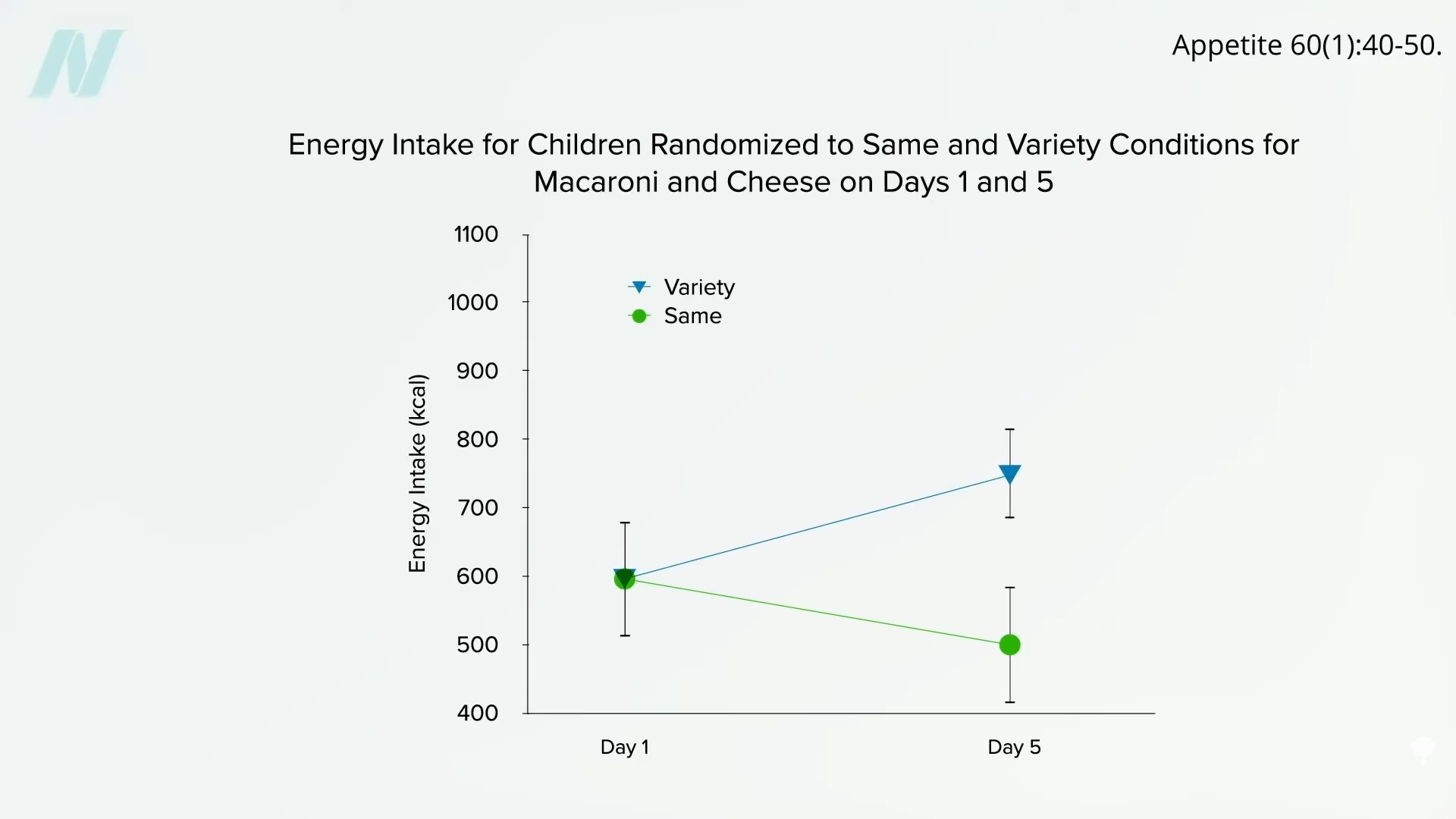

Whether foods are on the same plate, are at the same meal, or are even eaten on subsequent days, the greater the variety, the more we tend to eat. When kids had the same mac and cheese dinner five days in a row, they ended up eating hundreds fewer calories by the fifth day, compared to kids who got a variety of different meals, as you can see below and at 2:35 in my video.

Even just switching the shape of food can lead to overeating. When kids had a second bowl of mac and cheese, they ate significantly more when the noodles were changed from elbow macaroni to spirals. People allegedly eat up to 77 percent more M&Ms if they’re presented with ten different colors instead of seven, even though all the colors taste the same. “Thus, it is clear that the greater the differences between foods, the greater the enhancement of intake,” the greater the effect. Alternating between sweet and savory foods can have a particularly appetite-stimulating effect. Do you see how, in this way, adding a diet soda, for instance, to a fast-food meal can lead to overconsumption?

The staggering array of modern food choices may be one of the factors conspiring to undermine our appetite control. There are now tens of thousands of different foods being sold.

The so-called supermarket diet is one of the most successful ways to make rats fat. Researchers tried high-calorie food pellets, but the rats just ate less to compensate. So, they “therefore used a more extreme diet…[and] fed rats an assortment of palatable foods purchased at a nearby supermarket,” including such fare as cookies, candy, bacon, and cheese, and the animals ballooned. The human equivalent to maximize experimental weight gain has been dubbed the cafeteria diet.

It’s kind of the opposite of the original food dispensing device I’ve talked about before. Instead of all-you-can-eat bland liquid, researchers offered free all-you-can-eat access to elaborate vending machines stocked with 40 trays with a dizzying array of foods, like pastries and French fries. Participants found it impossible to maintain energy balance, consistently consuming more than 120 percent of their calorie requirements.

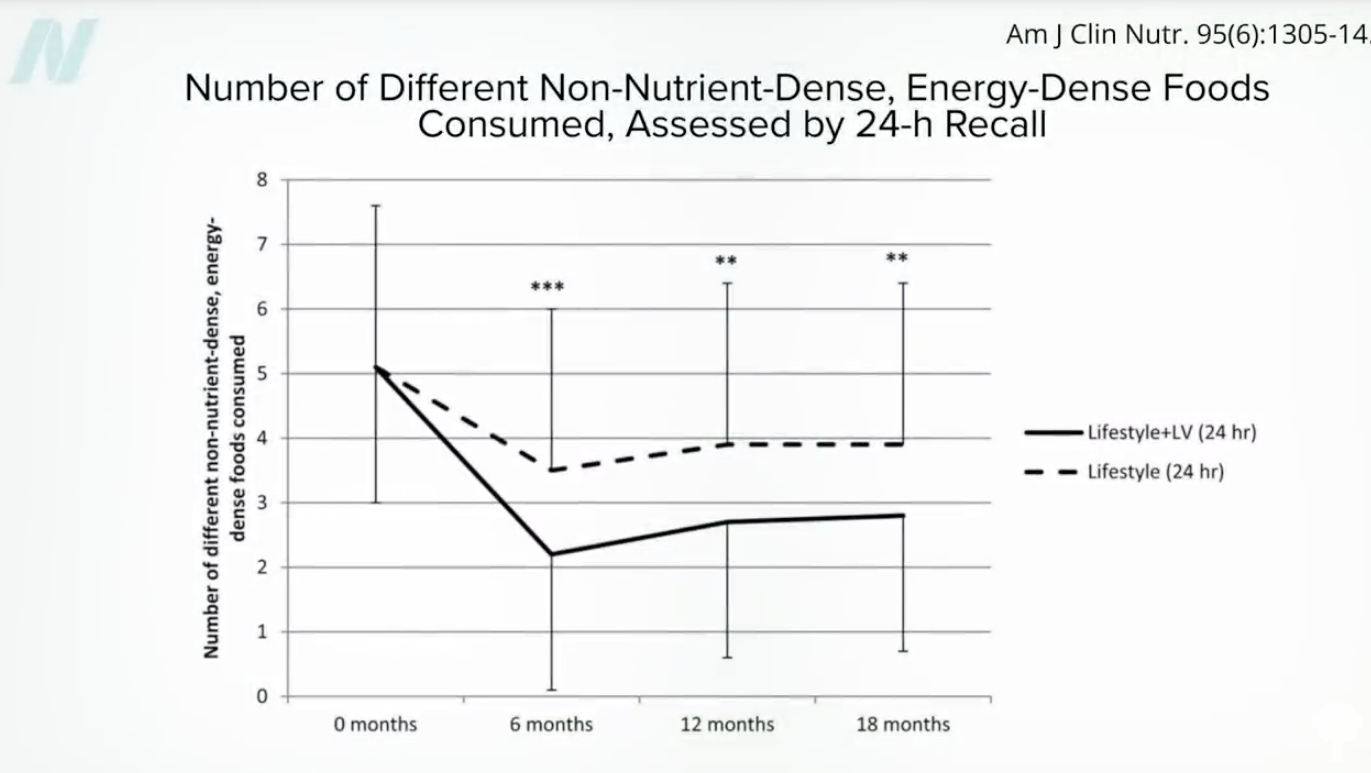

Our understanding of sensory-specific satiety can be used to help people gain weight, but how can we use it to our advantage? For example, would limiting the variety of unhealthy snacks help people lose weight? Two randomized controlled trials made the attempt and failed to show significantly more weight loss in the reduced variety diet, but they also failed to get people to make much of a dent in their diets. Just cutting down on one or two snack types seems insufficient to make much of a difference, as seen below and at 4:44 in my video. A more drastic change may be needed, which we’ll cover next.

Post Comment