Martin, like everyone else in Milwaukee, wanted to work at Schlitz. It was the second-best-selling beer in the U.S. behind Budweiser, its rival down in St. Louis. But Schlitz wasn’t the only brewery in town. Milwaukee was home to Pabst, Blatz, and Miller as well. And the big four powered the city like no other industry.

In fact, Milwaukee was such a scene that Hollywood took notice. In 1976, at the height of Schlitz’s popularity, ABC Television aired the first episode of Laverne & Shirley, in which stars Penny Marshall and Cindy Williams—sharing a cramped basement apartment in downtown Milwaukee—toiled in the bottling department of a Schlitz doppelgänger called “Shotz.” Fittingly, the sitcom ran until 1983, ending its run at right about the time Schlitz was decimated and sold off for parts to rival Stroh Brewery.

In a series of interviews several years ago at his home outside Kansas City, Martin, who died in 2023 at age ninety-three, reminisced about his days at Schlitz and recalled how he got his start at the company. Luck was on his side. Martin got on the radar of Paul Pohle, a Schlitz executive and former fraternity brother. Martin was hired right out of college in 1952 as a junior analyst in the market-research department. “I didn’t even know how to spell ‘market research,’ ” Martin admitted. “I had never even heard of it. I just wanted a sales job at Schlitz, but they wouldn’t put a guy under twenty-five in sales. They wanted someone with, as they put it, ‘established drinking habits’—which is hilarious.”

Thus, Martin took what he called a “crummy job” in market research at Schlitz for $300 a month. But timing worked in his favor. Just three years later, as Pohle climbed the corporate ladder, Schlitz executives needed a new head of the research department. None of the outside candidates impressed the muckety-mucks, so Martin got the promotion. “They didn’t give a shit who ran the research department,” he said in one of our interviews. “If it was [looked upon as] an important department, I wouldn’t have gotten it.”

That was just his first step up the ladder. Soon the ambitious Martin would be calling the shots on strategy and spearheading an escalation of the beer wars, with disastrous consequences.

Battling to Be No. 1

The big domestic brewers were engaged in an all-out war for brand supremacy long before Martin entered the fray. It was a blood sport that didn’t flow red and viscous but rather golden and frothy. But no two beer makers had a more vitriolic rivalry than Budweiser and Schlitz. Schlitz had been the best-selling beer in the U.S. in the early 1900s and again when Prohibition ended in 1933—by 1940 it dominated the market. But by the 1950s, it found itself tussling over the top spot with Budweiser. And in 1957, Bud passed Schlitz as the number-one-selling beer and held on to the advantage.

By the mid-1970s, when Martin was at the height of his power, Schlitz was tired of coming in second. Martin and his fellow executives decided it was time to shake things up and make a big play to take down Budweiser.

But to really understand the background of the beer wars, you first need to know the rules—the beer rules. Here’s the short version: If you make booze, you can sell it only to wholesale distributors. (The movie Smokey and the Bandit is based on this rule. Well, that and car chases.)

In the 1920s, Prohibition had ushered in a three-tier system for the sale of beer made up of producers, distributors, and retailers (in that order). Martin, in an interview, described it this way: “You have to have a license to brew beer, you have to have a license to wholesale beer, and you have to have a license to retail beer. And in most places, it’s illegal to have a license for more than one.”

Why the complications? Money, of course. Each tier can be subject to a variety of federal, state, local, and other taxes, which means more and more beer money is siphoned into government coffers. There were also a multitude of middlemen between the breweries and their customers.

The scheme ran deep. Schlitz kept two sets of books to conceal illicit payments, spending millions annually.

The combination of that Byzantine regulatory environment with the ferocious competition for sales naturally catered to hard-charging execs who knew how to work the system. Martin prided himself on being able to do just that. And the Astrodome incident is a prime example.

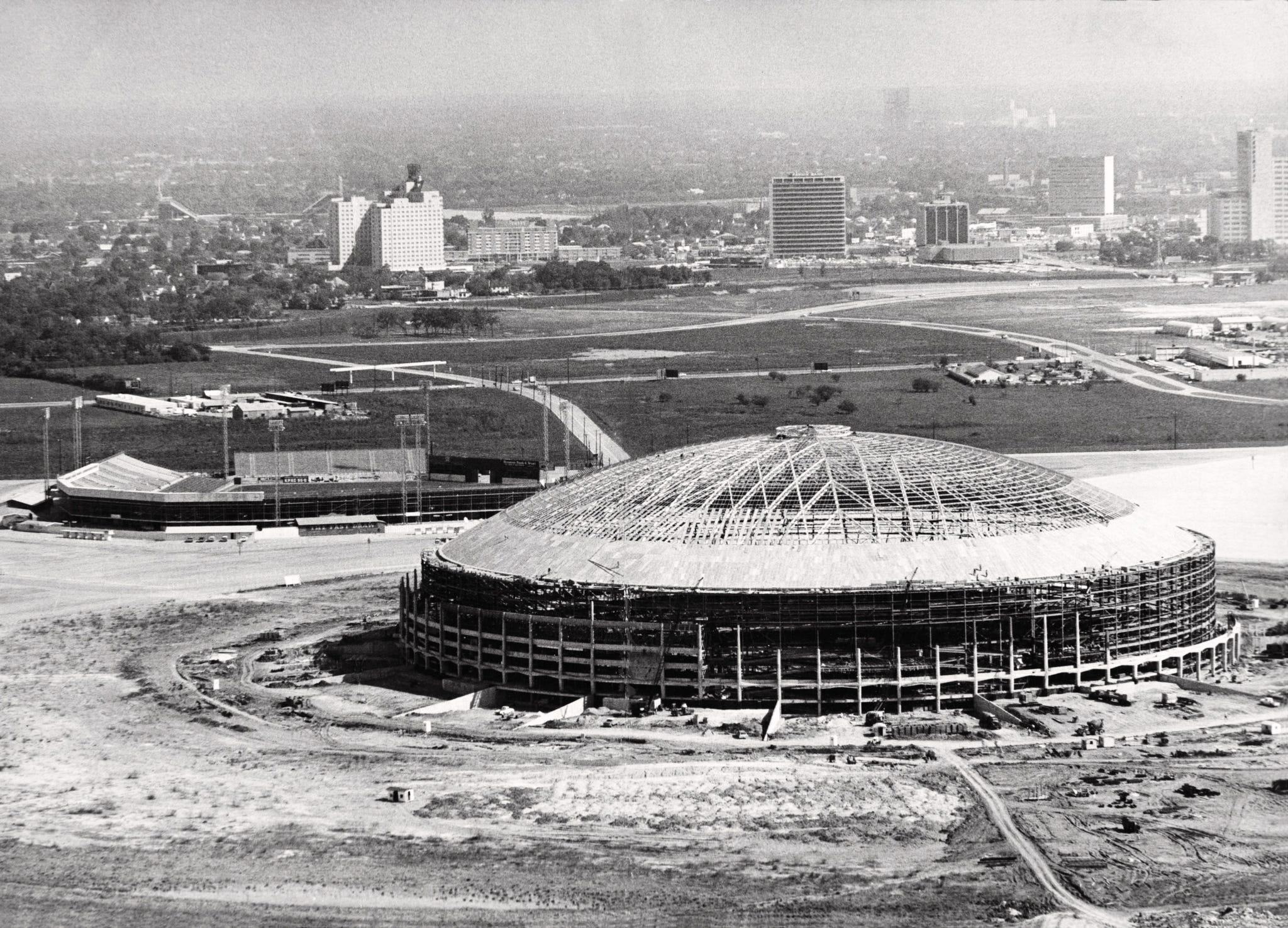

Remember the mysterious phone call about the baby arriving safe? Well, the guy who delivered that line turned out to be legendary Houston businessman Roy Hofheinz, a former mayor of the city. He and Martin had a cozy relationship. Colloquially known as “the Judge,” Hofheinz was the artful, cigar-chomping Texan owner of Houston’s Colt .45 baseball team and the brains behind constructing the Astrodome. Imagine Hofheinz as a mash-up of Lyndon B. Johnson and George Steinbrenner.

Because Martin was responsible for baseball sponsorships at Schlitz in the sixties, he and Hofheinz became not just close business acquaintances but personal friends. So naturally, Schlitz decided it would sponsor the new Houston baseball team (which would later become the Astros), providing Hofheinz got the Astrodome built. In Martin’s unpublished autobiography, he recalls a time when Hofheinz was $225,000 short to finish the Astrodome.

Hofheinz’s creditors were asking for payment on a prior loan, thus preventing him from securing the additional funding needed to get the stadium built. Hofheinz was out of options to secure financing; his entire financial empire was on the brink of collapse. Hofheinz spoke in code, telling Martin what Martin already knew: Under Texas law, Hofheinz couldn’t borrow a dime from Schlitz, because the brewery sponsored the broadcasts of Astros games.

Martin, ever the problem solver, then recalled: “It occurred to me that $225,000 was a remarkably small sum considering his total debt . . . that $225,000 was really less than what we were paying every quarter to him for the broadcast rights.”

Here’s where Martin veers into a gray area of legality. Martin recalled telling Hofheinz, “There would absolutely be nothing wrong legally or otherwise for us to simply pay you early for the next quarter [of broadcast rights], which is coming up in a few weeks anyway. And this should solve your problem without causing any trouble for us or for you, legally.”

Would it? No matter. Hofheinz was in a bind and instantly accepted the offer—Schlitz’s “early payment” for broadcast rights secured the funding needed for the stadium. Martin just needed the official green light from Uihlein, who immediately gave it. More than a decade later, the Astrodome would appear among the catalog of charges against Schlitz.

Two Sets of Books

If the Astrodome was a particularly dramatic instance of Schlitz’s prowess at under-the-table marketing, Martin and his compatriots had made it part of the company’s standard operating procedure by the mid-seventies. As federal prosecutors would later charge, Schlitz regularly paid inducements to secure dominance in “accounts of influence.” Think of it as payola for beer.

The Milwaukee Sentinel detailed how even minor transactions—like a Milwaukee sales manager funneling $1,208 for carpeting at Humpin’ Hannah’s Nightclub via an ad agency—were part of a broader money-laundering scheme. And who was at the center of this? Martin, of course. In one of our interviews, he recalled a cryptic call from a retailer warning him the FBI was coming for records linking Schlitz to bar refurbishments. Martin brushed it off. From his point of view, he was just doing business.

Post Comment