Unlock the Hidden Power Moves: Why the Traditional 60/40 Portfolio Could Be Costing You Millions and What to Do Instead

Let’s face it – defensive asset allocation isn’t your average walk in the park. It’s not as simple as slapping a global equity tracker on your portfolio and calling it a day. There’s no magical “dark times” asset class hiding under your bed, ready to shield your wealth from every possible economic curveball. You see, your portfolio is this delicate beast, constantly fending off a barrage of threats—surging inflation, deflation, that dreaded stagflation, recessions, and yes, those gnarly stock market bubbles that pop when you least expect them. So, what’s the game plan when the first line of defense crumbles? You better have a multi-layered strategy ready to soften those inevitable blows.

Here’s the kicker—your personal risk exposure steers the ship. Retirees, you’re staring inflation in the face, while the young and hungry might be sweating over job market crashes and recessions. The smart move? Bulk up on assets that directly tackle your own financial nemesis. It’s like gearing up for battle—know your enemy, then pick your weapons wisely. But beware: every asset has its quirks, and no defense is foolproof. Think of diversification as your best ally in the chaotic arena of investing—maybe your only ally, frankly.

If you’re ready to unpack the nitty-gritty of defensive assets, figure out which ones could actually hold the line, and avoid the traps most investors fall into, then stick around. There’s a lot to cover and more than a few surprises on the horizon.

Defensive asset allocation is trickier than the growth side of the equation. For the latter, you can just strap on a global equity tracker for portfolio propellant and be done with it. But there isn’t a universal ‘dark times’ asset class that reliably protects your wealth from economic misfortune.

A portfolio is exposed to multiple threat vectors: inflation, deflation, stagflation, recessions, and stock market bubbles. Fending that lot off requires a multi-layered defence. If the first line fails then perhaps the next will soften the blow.

Your choice is complicated by your personal risk exposure. For instance, inflation is typically a bigger threat to retirees than young people. The young are more exposed to recessions and periods of joblessness.

It makes sense therefore to strengthen where you’re personally most vulnerable – loading up on the assets most likely to counter your own financial arch-nemesis.

Know your enemy

Here’s a quick summary of portfolio pathogens paired with their most effective treatments:

| Threat vector | Best defensive asset | Worst defensive asset | Most exposed |

| Surging inflation, stagflation | Individual index-linked gilts, commodities, gold | Long bonds | Retirees |

| Deflation, recession, stock market drawdown | Nominal government bonds, cash, gold | Commodities | Mid-career, late-stage accumulators, aggressive equity investors |

| Currency debasement, sovereign debt crisis | Gold, assets priced in foreign currency | Domestic government bonds, cash | Investors heavily tilted towards domestic assets |

Handy though the table is, it’s missing nuance, and a generous sprinkle of ‘ifs’ and ‘buts’. Fear not: they’re coming next!

Gold, for example, looks like the ultimate wealth-preserver. I’ll have six sackfuls, please! But there are reasons to doubt it, too. (See the gold section below).

Also, just so we’re crystal clear:

- No asset class is risk-free or ‘safe’. Not even cash.

- No asset class is guaranteed to work on demand.

- Unexpected circumstances can nullify any defence.

- A defensive asset may come good but not immediately, nor for the entire duration of a crisis.

- Diversification is your best friend. Possibly your only friend in the capricious world of investing.

These negatives aren’t meant to crush morale before we get started. It’s just a bald statement of fact.

Hopefully things will go well for all of us. But it’s best to have the full picture in case they do not.

The historical record and inherent uncertainty about the future both point in the same direction: use every tool in the box.

The best defensive asset classes

Defensives are asset and sub-asset classes that can fortify your portfolio when equities go down. Each of the following can play a useful role:

Nominal high-grade domestic government bonds

(Also known as gilts in the UK)

Defends against: Demand-led slumps such as economic contractions, recessions, depressions, deflation, and stock market drawdowns.

Vulnerable to: Surging inflation and fast-rising interest rates.

Younger investors

Long maturities theoretically provide the best diversification for equity-heavy portfolios. Although it doesn’t always work out that way in practice.

Older investors

Favour shorter-dated bond maturities because longer-term government bonds are highly vulnerable to inflation and fast-rising interest rates. Such shorter-dated govies may be less effective in a downturn but offer a better overall balance of risks. They’re more resistant to spiralling inflation and interest rates.

Diversification options

Global government bonds hedged to the pound

Pros: Diversification across advanced economy government debt. Choose if you’re wary of having 100% exposure to the credit risk of the UK Government. Hedge them to offset the risk of adverse currency movements that swamp your bond returns.

Cons: Higher OCFs than gilt funds. Less crash protection due to lower durations. Indices tilt towards high-debt countries such as Japan, Italy, and the US.

Pros: Often outperform gilts in a crisis because dollar-denominated assets are viewed as a safer haven.

Cons: Currency risk means they can underperform at just the wrong time. Also US political risk.

High-grade corporate bonds

Pros: Offer higher yields than government bonds.

Cons: Corporates don’t perform as well as govies during most downturns. Essentially because countries can withstand economic peril better than companies.

Individual nominal gilts

Pros: Opportunity to target particularly useful bond issues. For example, investing in specific gilts can reduce your tax burden outside of tax shelters. Extremely long maturities may be especially potent equity diversifiers. No management or platform fees.

Cons: Require more hands-on management and a good understanding of bond mechanics. Not all brokers enable you to invest online.

Useful to know

High-grade (or high-quality) refers to bonds with a credit rating of AA- and above (or Aa3 in Moody’s system). Check out our bond terms post.

Bond maturity / duration: a brief guide to risk

The following table sketches out the three term-related bond risk categories:

| Bond maturities | Volatility | Suits | Yield / expected returns |

| Short (0-5 yrs) | Lower | Older investors, lower equity allocations, higher inflation concerns | Lower, cash-like at the shortest end of scale |

| Intermediate | Middle ground | Middle ground | Middle ground |

| Long (15+ yrs) | Higher | Younger investors, higher equity allocations, lower inflation concerns | Higher, but possibly not worth the extra risk |

Longer maturities imply longer durations, though other factors are in play as well.

Duration is the key metric when judging high-grade government bond risk. Your bond’s duration number is an approximate guide to how big a gain or loss you can expect for every 1% move in its yield.

For example, if a bond’s duration number is 11, then it:

- Loses approximately 11% of its market value for every 1% rise in its yield.

- Gains approximately 11% for every 1% fall in its yield.

Read our piece on rising yields to understand how bonds respond when interest rates rise.

Index-linked government bonds (high-grade, domestic)

(Also known as ‘linkers’ in the UK)

Defends against: Inflation. Index-linked bonds also generally do okay in recessions but they aren’t as effective as nominal bonds.

Vulnerable to: Fast-rising interest rates (see below). Deflation – index-linked gilts lose nominal value when the RPI index falls as they lack a ‘deflation floor’. On the other hand, they won’t lose real value in this scenario, which is what counts most.

Snag: Index-linked bond funds can be real-terms losers in inflationary periods. That happens when steep interest rate hikes cause fund prices to drop. Sometimes the resultant capital loss is so severe that it drowns out the inflation-adjusted gains of the fund’s underlying bonds. The problem is solved by investing in individual index-linked gilts.

Individual linkers hedge inflation if held to maturity. Linkers still fall in price when interest rates rise but will make good the capital loss by their maturity date. Ignore that paper loss and each linker will ultimately return RPI plus the real yield on offer when you bought in.

In contrast, bond funds routinely sell their holdings before maturity. This causes losses in rising rate conditions (and gains when rates fall). The process doesn’t doom index-linked bond funds to lose against an equivalent portfolio of individual linkers over time. But it can make them a relatively poor inflation hedge.

Beware that if you buy individual linkers on negative yields – and hold to maturity – then you’re accepting an annual loss in exchange for broader inflation protection. In this scenario, the bond’s link to RPI means its value will rise to match inflation. However, the price you’d pay here for that inflation matching would be the negative real yield at the time of purchase.

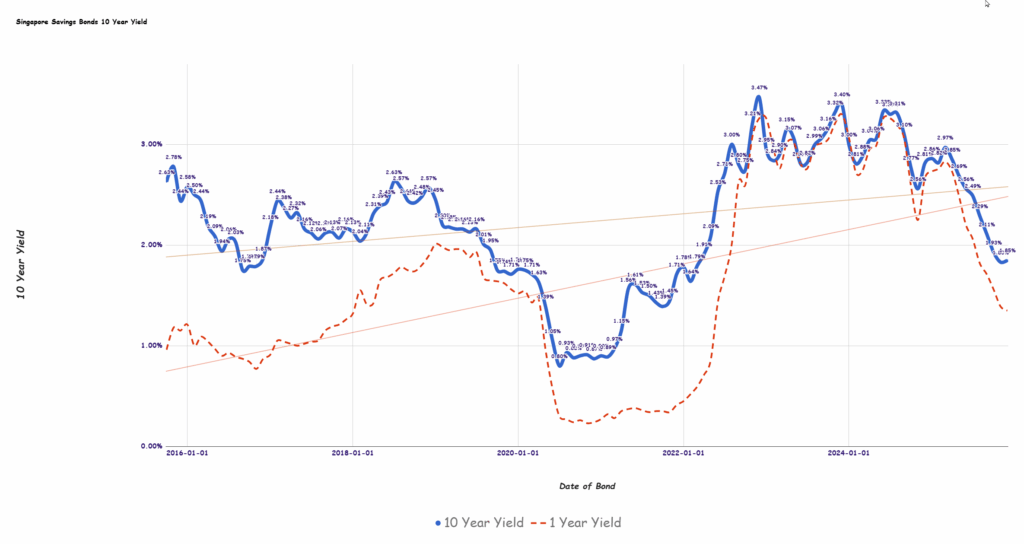

Thankfully, real yields are now positive, so you’re covered against double-digit rises in inflation and you can make a small annual profit on top.

Younger investors

Can ignore index-linked gilts on the grounds that equities outperform inflation in the long run.

Older investors

Individual index-linked gilts held to maturity are the most reliable way to hedge inflation. If you use funds to hedge inflation then choose short-dated ones because long bonds are hit harder by soaring rates.

Useful to know: Don’t get hung up on index-linked gilts lacking a deflation floor. The UK hasn’t experienced annual deflation since 1933.

Diversification options

Short-term global index-linked funds hedged to the pound

Pros: Off-the-shelf convenience. Should outperform nominal bond equivalents during bouts of unexpected inflation.

Cons: Other countries’ inflation rates won’t perfectly match the UK’s. Interest rate risk interferes with inflation-hedging capability as described above. Currency risk issues if the fund isn’t hedged to GBP.

- For options, see the Global inflation-linked bonds hedged to £ section of our low-cost index funds page.

Index-linked gilt funds

Pros: May perform when interest rate rises aren’t a major factor. Aligned with UK inflation. No currency risk.

Cons: Almost all UK index-linked gilt funds have long average maturities / durations. An exception is iShares Up to 10 Years Index Linked Gilt Index Fund. Its lower duration places it on the outer rim of the short-term choices.

Individual index-linked gilts

Pros: Specifically designed to hedge UK inflation if held to maturity. No management or platform fees.

Cons: Require more effort to manage than bond funds. Not all brokers enable you to invest online.

Physical gold

Defends against: Stock market drawdowns, surging inflation, recessions, simultaneous falls in equities and bonds.

Vulnerable to: Volatility, small changes in demand, lack of fundamental value, myth-making.

Snag: Gold’s versatility looks incredible – like the everything burger of defensive assets. Yet there are reasons to be wary.

For one thing, gold’s track record as an investible asset is relatively short. That’s because it was subject to government control until 1975.

This means that unlike with bonds and cash, we can’t see how the precious metal performed during World Wars, depressions, and multiple inflationary episodes. There’s a danger that gold’s impressive history is flattered by a small sample bias. (Gold has only racked up 50 years as an investible asset class versus more than 150 years for other defensives.)

Moreover, beware being bedazzled by gold’s recent amazing run. Dig a little deeper and you’ll see that the yellow stuff fell 78% in real terms from 1980 to 1999.

Another concern is that physical gold returns aren’t linked to intrinsic value. Equities provide a claim on the future cash flows of productive businesses. Government bond interest is paid by tax revenues. Even commodity profits can be traced back to ‘roll return’ and interest on collateral.

In contrast, your gold gains are dependent on someone deigning to offer you a higher price than you bought in for.

Thus it’s worth asking if current gold prices are sustainable? Are they being driven by fundamental sources of demand? Or are waves of performance-chasers being suckered in by a succession of all-time highs? What happens when gold’s momentum falters?

The irresolvable nature of these questions underlies my caution about gold. For a (much) deeper discussion see the excellent Understanding Gold paper by Erb and Harvey.

Younger investors

Consider a 5-10% allocation for diversification purposes.

Older investors

Consider a 5-15% allocation for diversification purposes. Remain wary of overcommitting due to the question marks hanging over gold’s short track record and its high current valuation levels.

Diversification options

Gold miners: You’d have to be insane to think of miner stocks as a defensive asset class.

Gold future ETCs: WisdomTree Gold (Ticker: BULL) invests in gold future’s contracts and has seriously underperformed its physical counterparts since inception.

Silver: Appears to be a less powerful defensive diversifier because demand is more closely tied to economic activity.

Broad commodities

Defends against: Surging inflation.

Vulnerable to: Recessionary conditions.

Snag: Commodities are highly volatile and typically a liability during economic contractions when demand evaporates for raw materials. Diversification is key so choose broad commodity ETFs not single commodity funds.

Younger investors

Can ignore commodities on the grounds that equities outperform inflation over time.

Older investors

Potentially the best portfolio diversifier against inflation. Whereas index-linked gilts match inflation by design, commodities can massively outperform by nature. Commodities are especially potent when the cause of the price shock is global supply chain shortages – as occurred after each World War and post-Covid.

Diversification options

Single commodity ETCs

Pros: None – excessive idiosyncratic risk.

Cons: Studies show that a basket of diversified commodities significantly outperforms any single commodity over the long-term.

Commodity equities

Pros: None as a defensive portfolio diversifier.

Cons: Too correlated to the stock market.

Cash

Defends against: Demand-led slumps such as economic contractions, recessions, depressions, deflation, and stock market drawdowns.

Vulnerable to: Inflation, low interest rates.

Snag: Cash has delivered the lowest historical returns of any of the defensive diversifiers on our menu. Carrying too much cash will probably hold back your portfolio over time.

Younger investors

The flight-to-quality effect means longer-dated bonds are more likely to prop up an equity-dominated portfolio in a crisis.

Older investors

Cash is a useful complement to bonds. Cash won’t spike in value during a crisis but neither will it plummet when interest rates rocket. But beware the ‘money illusion’ effect when interest rates look good but are largely wiped out by inflation.

Diversification options

Money market funds (MMFs)

Pros: Highly responsive to interest rates. There’s no need to keep on top of Best Buy tables when interest rates are rising because MMFs automatically reinvest into higher-yielding securities. The opposite is true when rates are falling.

Cons: Riskier than cash. Money market funds can struggle to meet investors’ demands for their money back under extreme conditions. MMFs aren’t covered by the FSCS bank guarantee. (Your platform may be covered by the FSCS investor compensation scheme.) Management and platform fees.

Pros: Like money market funds they are highly responsive to interest rates. Backed by the UK Government so safer than MMFs.

Cons: Must be held to maturity – usually one, three, or six-monthly terms. Not covered by the FSCS bank guarantee. (Your platform may be covered instead.) Platform fees.

Defence in depth

If you’d like to see the multi-layered defence concept in action then check out our posts on:

Ultimately, a simple equity/bond portfolio was shown to be too simple by the events of 2022. Just swapping nominal bonds for cash is probably not ideal either. Money market funds have been soundly beaten by bonds in the long run.

What we know for sure is that all of the defensive asset classes we’ve covered above work some of the time. But none of them work all of the time.

They each have uses and flaws. As we never know what’s coming around the corner, the answer is surely diversification.

Take it steady,

The Accumulator

Post Comment